This is also posted on Reads4Tweens, where I have a list of fairytale books I’ve reviewed. I’ve marked books that I think appeal equally to boys and girls, regardless of what the cover looks like. Jessica Banks also has an interesting post on boys and fairytales.

When did fairytales end up being for girls? Is this something the Disney Princess marketing juggernaut created or something it just cashed in on?

A quick tangent: As a mom, a teacher, and a book reviewer, I twitch a little when I click the “Boy Appeal” or “Girl Appeal” button to categorize a book on this site. “Well then why do I even have that button?” you might ask (and I’ll be happier imagining it asked in Dr. Doofenshmirtz’s voice). Because it’s sort of useful as a general categorization, and for better or worse, some books are aimed squarely at either girls or boys. I don’t use it all that much, and if I’m honest, I use it only as it relates to boys. If a book seems to make no accommodation whatsoever for a male reader, I mark it “Girl Appeal.” If a book has a girly look to it or a female protagonist but really might also appeal to a lot of boys, I mark it “Boy Appeal.” In a quest for some kind of parity I can’t actually defend, I also mark stereotypically boyish books as “Boy Appeal” but I can do that feeling fairly certain that few girls will be chased off by that designation. And lots of books get marked both “Boy Appeal” and “Girl Appeal” which makes you wonder why I bothered.

Anyway, I bring that up because we seem to have this need to have boy books and girl books, but it’s inherently problematic to try to split books up like that. That’s probably a rant for another day. To get back to my original rant, I don’t understand how fairytales came to be so very strongly in the girl book category. I have my suspicions and they all have to do with selling princess stuff to little girls, but that’s still doesn’t seem to quite explain it.

In A Tale Dark and Grimm, the author repeatedly reminds us that fairytales are awesome—and by awesome he means full of action, gore, and scary things. And he’s totally right…well, maybe not about the “awesome” part, at least in my book. But fairytales are full of gore, and things that eat children, and creepy people and creatures, and violence and bloodshed and all the other stuff you stereotypically expect from games, books, and movies aimed at boys. You know what else they’re full of? Male protagonists. In fact, if one of our big complaints about fairytales is that the heroines are so passive, then doesn’t it stand to reason that if the plot moves along there must be at least a few active heroes? (The Hero’s Guide to Saving Your Kingdom has an amusing take on how princesses have stolen the stories from the princes.)

So why are fairytales the realm of girls? Almost all of the fairytale retellings clearly target girls. And some of them really are about princesses and balls and romance and pink castles in the clouds, and that is all very stereotypically girly. But a lot of them have wonderful male and female characters, and a sense of humor, and sometimes cyborgs or demons or dragons. In other words, they’re great stories for kids who like fantastical stories.

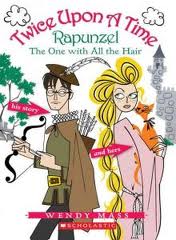

I recently read and thoroughly enjoyed Wendy Mass’ Rapunzel: The One With All the Hair. It’s from her Twice Upon a Time series, which tell familiar fairytales from the point of view of the hero and the heroine at the same time through alternating chapters. So a full half of the book is from the point of view of the prince, an engaging and amusing young hero. My daughter, of course, loved it. Guess what? So did my son. I borrowed the book through Booksfree, which luckily meant I got the older cover, which looks like this:

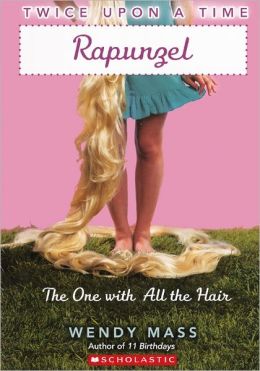

It features both characters, and it doesn’t really scream “GIRL” in your face. I’m not saying it’s gender-neutral—I think it probably would appeal to more girls than boys. But at least it doesn’t scream “THIS ISN’T FOR YOU GO FIND SOMETHING ELSE WHY WOULD YOU EVEN LOOK AT THIS” like the new cover does:

Now, my boy isn’t too stereotypically boyish. He’s headed more toward the longhaired poet with a guitar, or maybe the mad scientist, than he is toward quarterback of the football team. With a slightly older sister, he’s embraced some things that might send a less secure boy screaming from the room to go blow up some virtual bad guys. But I don’t think even he would have touched a book with this cover—the same book that he enjoyed, that made him laugh out loud.

What is the purpose of closing this book off to boys? Why, oh why, are fairytales only for girls? When there are numerous studies about how it’s hard to get many boys to read, when parents and teachers everywhere search for engaging books, why ensure that half the potential readers wouldn’t touch this clever book with a ten foot pole?

(You know what? It turns out that this cover doesn’t even appeal to my girl. She’d seen this book in the bookstore and passed it up, assuming it was some clunky modern retelling. You can see why, based on the flippy skirt and hand on the hip.)

I understand the appeal of rereleasing a book with a new cover. Yes, we do judge books by their covers, and you can reach new readers by presenting a new image. But was it really impossible to design a cover that wouldn’t alienate boys? To design a cover that would hint at both clever characters within?

I want to cover this book in brown paper, so maybe at least a few boys will discover the fun that is Rapunzel: The One With All the Hair. Even though, apparently, fairytales are for girls.

Addendum

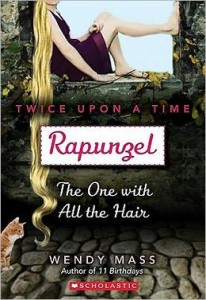

While collecting the images for this, I came across a third cover. It bothers me less that the PINK one and it appeals a lot more to my daughter, but it still leaves off the prince and, inexplicably, Rapunzel is still missing an actual head. Just hair. No head. Make of that what you will. (And here’s a article that makes a lot of the headless girl cover trend, as well as other disturbing trends in book covers aimed at young female readers.) For the record, my daughter’s favorite cover is the first one—the one with both characters and their heads.